Election season is starting up again, and as with many other topics I’m seeing a lot of overconfident takes from people in tech wanting to “solve” how voting works with naïve techy solutions. Hell, even a presidential candidate seems to have proposed an extremely uninformed plan for “fixing” voting using blockchain technology.

Last year I wrote a thread on Twitter covering some of the essential properties good voting systems uphold as well as how they prevent fraud. It was through the lens of Alameda County’s voting system, where I’ve volunteered as a poll worker in the past (and intend to do again). I’ve been meaning to write down the contents of that thread in blog form for a while, and now seemed like a good opportunity to do it.

I’ll be explaining more about most of these properties later, but ideally, a good voting system should uphold:

- Secret ballot: Nobody, not even you, can verify who you voted for after you’re out of the polling place, to prevent vote-buying and coercion.

- Auditable paper trail: We should be able to audit the election. Paper trails are usually the most robust way to enable effective audits.

- Obviousness: It should be relatively obvious what individuals should be doing when they need to mark their ballots. A system that you can easily “mess up” with is a bad system.

- Accessibility: It should not exclude individuals with disabilities from being able to vote.

How voting works in Alameda County

I’ll first go over how voting in my county works. The system isn’t perfect, but it’s pretty good, and it’s a good springboard for understanding how voting systems in general can work. There’s a poll worker guide you can refer to if you’re really interested in all the specifics.

Broadly speaking, there are four ways to vote:

- By mail

- In person at certain government offices, before election day (“early voting”)

- In person on election day at a polling place

- Provisionally, in person on election day at a polling place

Voting by mail is pretty straightforward: When you register you can choose to vote by mail (or you can choose to do so online after the fact). You get a ballot in the mail, along with a special envelope. You fill in the ballot at your leisure, stick it in the envelope, write your name/address on the envelope, sign it, and mail it back. There are also convenient ballot dropboxes all over the place in case you’re a millenial like me and don’t want to figure out how to buy stamps1.

If you’re voting by mail you can also show up at any polling place on the day of the election and drop off your ballots in a sealed bin. At the polling place I helped run roughly half of the people coming in were just there to drop off their vote by mail ballots!

Voting by mail is by far the easiest option here. Sadly not all counties support it2. In some states this is even the default option.

As I understand it, voting in person at designated government offices3 is pretty much the same as voting in person at a polling place, it’s just run by government employees instead of volunteers and open for a few weeks before election day.

Poll workers are given some neat bling to wear

In person voting

If you’ve chosen to vote in person, you are supposed to turn up at your assigned polling place (you get your assignment in the mail along with other voter info booklets).

There’s a copy of the list of people assigned to the polling place posted outside, and another with the poll workers inside. When you tell your name to the poll workers, they cross your name off the list, and you have to sign your name next to it4.

- If your name isn’t on the list, the poll workers will try and find your assigned precinct and inform you that you can go there instead, but you can still choose to vote provisionally at the existing precinct.

- If your name isn’t on the list of all voters (perhaps you registered very late, or were unable to register), you can also vote provisionally.

- If your name is on the list but marked as voting-by-mail (and you want to vote in person), you can vote normally only if you surrender your mail ballot (which poll workers will mark as spoiled and put in a separate pouch).

- If you lost/didn’t receive your ballot, you can always vote provisionally.

When you are voting normally, signing your name on the list fraudulently is illegal.

If it is your first time voting, you need to show some form of ID, but it doesn’t need to be photo ID and even a utility bill is fine.

Once you’re done signing, you’ll be given your ballot cards and a privacy sleeve folder so you can carry your filled ballots around. Because this is California and there are tons of local and state measures, we had 4 (!!) ballot cards, six sides to fill in5. Usually a poll worker will also detach the ballot stubs in front of you and hand them to you to keep. You can use these to check the status (but not the contents!) of your ballot online.

You take your cards to a voting booth, fill them in, and come back. A poll worker will then help you feed your ballot cards into a scanner machine. This machine will reject cards with any problems — which you can fix, rerequesting new ballot cards if necessary, but you then have to spoil and return the old ballot card.

The machine keeps an externally-visible tally of the number of ballots submitted, and an internal tally of all the votes made, ignoring write-ins. It also internally stores ballot cards in one of two bins (depending on write-ins). These bins are verified to be empty when polls open, and are inaccessible till polls close.

It’s important to note that the scanner is not a load-bearing component of the system: It could be replaced with a locked bin with a slot, and the system would still work. The scanner enables one to get preliminary results for the precinct, and provides a way to double-check results.

And that’s it! You’ll be given an I Voted sticker, and you can go home!

Some “I Voted!” stickers in Spanish

Using a voting machine

In case you think you will have trouble filling out a ballot card in pen (e.g. if your vision is heavily impared), there’s an alternate way to vote that doesn’t involve a pen. Instead, we have a machine which has a touchscreen and an audio unit, which prompts the voter for their selection for each ballot item on the touchscreen or audio unit. When they’re done, the machine will print out a “receipt” listing their choices inside a sealed box with a glass window, so they can verify that their vote was recorded correctly6. Once they’re done the sealed box will scroll the “receipt” out of view so that the next voter can’t see it.

The sealed box is called a Voter-Verified Paper Trail box: the election runners no longer need to trust the machine’s internal memory, they can trust the paper trail inside the box (which, while produced by a potentially-untrustworthy machine, was verified by the voters), and the machine’s internal memory is simply a way to double-check (and get fast preliminary results).

Provisional voting

There are many, many situations in which you may not be able to vote normally. Perhaps you showed up at the wrong precinct but don’t have time to go to the right one. Perhaps you were signed up for vote-by-mail but didn’t receive (or lost) your ballot. Perhaps you recently moved into the county and weren’t able to register in time. Perhaps you were a first-time in-person voter and didn’t have some form of ID.

In such a case you can always vote provisionally. The beauty of this system is that it removes most liability from poll workers: we don’t have any reason to turn people away from the polls, all we can do is refuse to let people vote normally (and instead vote provisionally) in the case of any inconsistencies. This is not to say that malicious poll workers can’t turn people away; it’s illegal but it happens. But well-meaning poll workers cannot, by accident, disenfranchise a voter because we are always allowed to give them a provisional ballot, and that’s an easy rule to follow.

With provisional voting, the voters are given the same ballot cards, but they’re also given an envelope with a form on it. This envelope is equivalent to a voter registration form, (re)registering them in their appropriate county/district7. They vote on the ballot cards normally, but instead of submitting the ballots to the scanner, they put them in the envelope, which goes into a sealed bin8. You’re also given a number you can call to check the status of your ballot.

When you vote provisionally, the registrar of voters will manually process your envelope, remaking your ballot on the right set of cards if necessary, and feeding them into a scanner machine.

Integrity checks

Underlying this system is a bevy of integrity checks. There’s an intricate seal system, with numbered seals of varying colors. Some are to be added and never removed, some are to be removed after checking the number, some are never supposed to be touched, some are added at the beginning of the day and removed at the end of the day.

For example, during setup we check that the bins in the scanner are empty, and seal it with a numbered seal. This number is noted down on a form, along with some numbers from the scanner/touchscreen display. The first person to vote is asked to verify all this, and signs the form along with the poll workers.

Election officials drop in multiple times during the day, and may check these numbers. At the end of the day, the numbers of all seals used, and any physical seals that were removed are sent back along with all the ballots.

Various ballot counts are also kept track of. We keep track of the number of provisional ballots, the number of submitted regular ballots (also kept track by the scanner), the number of ballot cards used, and the number of unused ballots left over. Everything needs to match up at the end of the day, and all unused ballots are sent back. These counts are also noted down.

Poll watchers are allowed to be around for most of this, though I think they’re not allowed to touch anything. I think poll watchers are also allowed to be around when the actual ballots are being counted by election officials.

Immediate local results

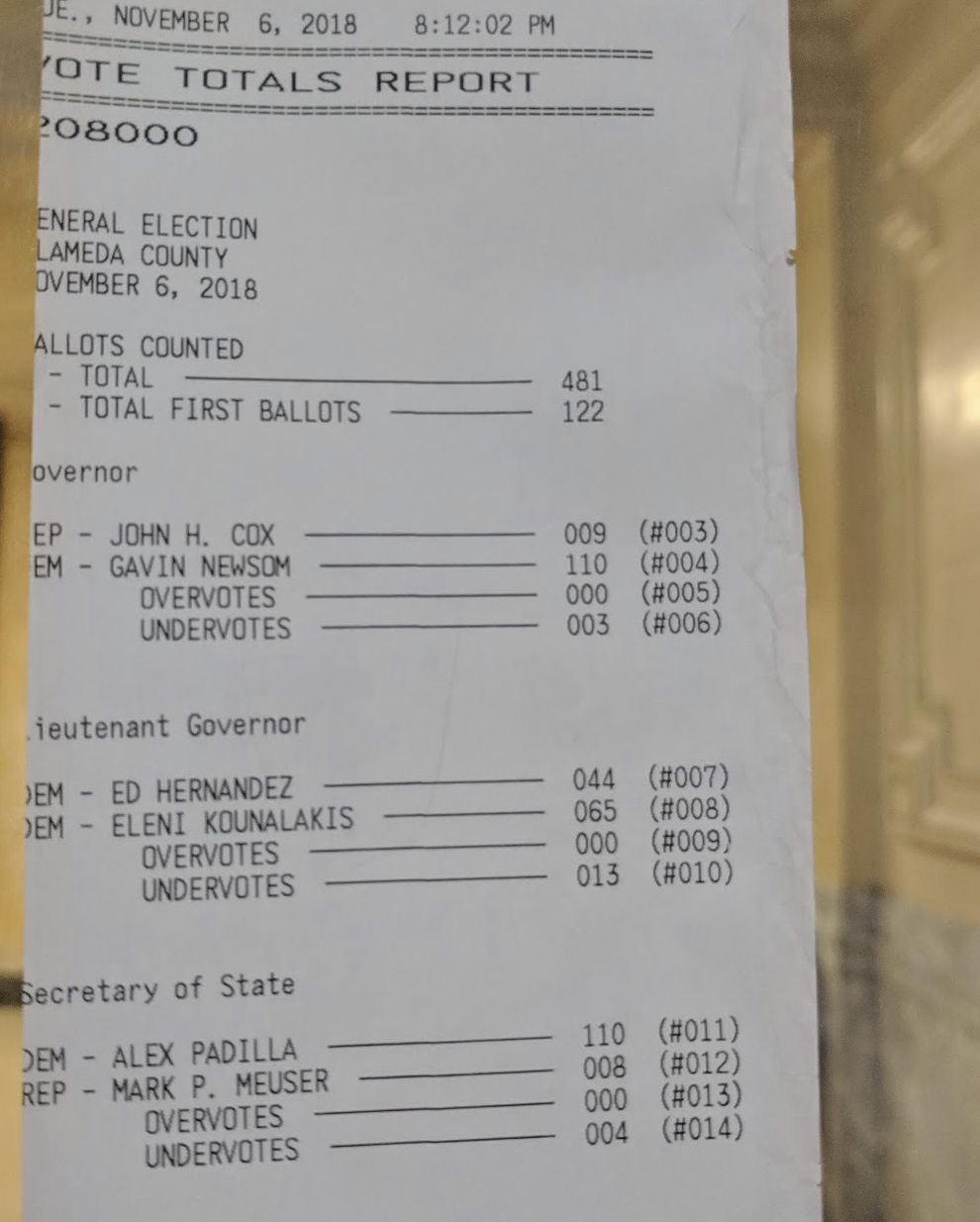

As mentioned before, the scanner isn’t a crucial part of the system, but if it happens to be working it can be used to get immediate local results. At the end of the day, the scanner prints out a bunch of stuff, including vote totals for races which got more than N votes (N=20, IIRC), so you get immediate results for your precinct. This printout is supposed to be taped to the polling place doors for everyone to see, and presumably the registrar of voters uses the copy submitted to them to publish quick preliminary results.

Using paper ballots doesn’t mean that we have to give up all the benefits of computers doing some of the work for us! We can still use computers to get fast results, without relying on them for the integrity of the system.

Vote totals posted outside. Our ballots are big and have lots of races on them; so the list of vote totals is absolutely ginormous.

Properties of this voting system

This system has some crucial properties.

Secret ballot

It’s well known that nobody is supposed to be able to see who you voted for. But a crucial part of this system is that, once you submit your ballots, you can’t see who you voted for either. Of course, you probably can remember, but you have no proof. On the face of it this sounds like a bad property — wouldn’t it be nicer if people could verify that their vote was counted correctly?

The problem is that if I can verify that my vote was counted correctly, someone else can coerce me into doing this in front of them to ensure I voted a certain way. Any system that gives me the ability to verify my vote gives people who have power over me (or just people who want to buy my vote) the same ability.

Provisional voting doesn’t quite have this property, but it’s supposed to be for edge cases. Vote by mail trades off some of this property for convenience; people can now see who you voted for while you’re voting (and the people you live with can fradulently vote on your behalf, too).

Conservation of ballots (Auditable paper trail)

The total number of ballots in the system is roughly conserved and kept track of. If you’re registered to vote by mail, you cannot request a normal ballot without surrendering your vote by mail ballot and envelope (which we mark as spoiled and put in a separate pouch). If you re-request a ballot card because you made a mistake, the old card needs to be similarly spoiled and put away separately. It’s one set of ballot cards per voter, and almost all potential aberrations in this property result in a provisional vote9. Even provisional votes are converted to normal ballot cards in the end.

Eventually, there will be a giant roomful of ballots that cannot be traced back to their individual voters, but it can still be traced back to the entirety of the voters — it’s hard to put a ballot into the system without a corresponding voter. This is perfect — the ballots can be hand-counted, but they can’t be individually corellated with their respective voters.

You don’t even need to recount the entire set of ballots to perform an audit, risk limiting audits are quite effective and much more efficient to carry out.

Paper ballots

The fact that they can (and should) be hand counted is itself an important property. Hand counting of ballots can be independently verified in ways that can’t be done for software. Despite not being able to trace a ballot back to its voter, there still is a paper trail of integrity for the ballots as a bulk unit.

This property leads to [software independance]: while we may use software in the process, it’s not possible for a bug in the software to cause an undetectable error in the final vote counts.

Specific vote totals for the top races

Obviousness

Figuring out what to do in the voting booth isn’t hard. You’re allowed to request assistance, but you’ll rarely have to. There are systems (like the scanner’s error checking) that are designed to ensure you don’t mess up, but the system is quite sound even without them; they just provide an additional buffer.

Compare this with the problems some Texas voting machines had last midterm. The machines were somewhat buggy, but, crucially, there was an opaque right and wrong way to use them, and some voters accidentally used it the wrong way, and then didn’t check the final page before submitting. This kind of thing should never happen in a good voting system.

It’s really important that the system is intuitive and hard to make mistakes in.

Fraud prevention

So, how is this robust against fraud?

Firstly, voter fraud isn’t a major problem in the US, and it’s often used as an excuse to propagate voter suppression tactics, which are a major problem here.

But even then, we probably want our system to be robust against fraud.

Let’s see how an individual might thwart this system. They could vote multiple times, under assumed identites. This doesn’t scale well and isn’t really worth it: to influence an election you’d need to do this many times, or have many individuals do it a couple times, and the chance of getting caught (e.g., the people who you are voting as may come by and try to vote later, throwing up a flag) and investigated scales exponentially with the number of votes. That’s not worth it at all.

Maybe poll workers could do something malicious. Poll worker manipulation would largely exist in the form of submitting extra ballots. But that’s hard because the ballot counts need to match the list of voters. So you have the same problem as individual voters committing fraud: if the actual voter shows up, they’ll notice. Poll workers could wait till the end of the day to do this, but then to make any kind of difference you’d have to do a bulk scan of ballots, and that’s very noticeable. Poll workers would have to collude to make anything like this work, and poll watchers (and government staff) may be present.

Poll workers can also discard ballots to influence an election. But you can’t do this in front of the voters, and the receptacles with non-defaced ballots are all sealed so you can’t do this when nobody is watching without having to re-seal (which means you need a new numbered seal, which the election office will notice). The scanner’s inner receptacle is opened at the end of the day but you can’t tamper with that without messing up the various counts.

Election officials have access to giant piles of ballots and could mess with things there, but I suspect poll watchers are present during the ballot sorting and counting process, and again, it’s hard to tamper with anything without messing up the various counts.

Overall, this system is pretty robust. It’s important to note that fraud prevention is achieved by more social means, not technical means: there are seals, counts, and various properties of the system, but no computers involved in any crucial roles.

Techy solutions for voting

In general, amongst the three properties of “secret ballot”, “obviousness”, and “auditable paper trail”, computer-based voting systems almost always fail at one, and usually fail at two.

A lot of naïve tech solutions for voting are explicitly designed to not have the secret ballot property: they are instead designed specifically to let voters check that what their vote was counted as after the election. As mentioned earlier, this is a problem for vote-buying and coercion.

It’s theoretically possible to have a system where you can ensure your ballot, specifically, was correctly counted after the election, without losing the secret ballot property: ThreeBallot is a cool example of such a system, though it fails the “obviousness” property.

Most systems end up not having an auditable paper trail since they rely on machines to record votes. This is vulnerable to bugs in the machine: you end up having to trust the output of the machine. Buggy/vulnerable voting machines are so common that every year at DEFCON people get together to hack the latest voting machines, and typically succeed.

Voting machines can still produce a paper trail: Voter-Verified Paper Trail systems partially succeed in doing this. They’re not as good with maintaining the “conservation of ballots” property that makes tampering much harder, and they’re not as good on the “obviousness” part since people need to check the VVPAT box for what their vote was recorded as.

Ballot-Marking devices are a bit better at this: These still produce paper ballots, it’s just that the ballot is marked by the machine on your behalf. There’s still a bit of an “obviousness” fail in that people may not double check the marked ballot, but at least there’s a nice paper trail with ballot conservation! Of course, these only work if the produced ballot is easily human-readable.

It’s not impossible to design good voting systems that rely on technology, but it’s hard to maintain the same properties you can with paper ballots. If you want to try, please keep the properties listed above in mind.

Blockchain?

Every now and then people will suggest using blockchains for voting. This is a pretty large design space, but …. most of these proposals are extremely naïve and achieve very little.

For one, most of them are of the category that lose the “secret ballot” property, instead producing some kind of identifier you’re able to check in some published blockchain. This lets you see what your vote was after the election, and as I’ve covered already that’s not a good thing.

Even if this process only lets you verify that your vote was counted (but not what it was), it typically involves some understanding of cryptography to spot-check the validity of the machine output (e.g. you need to verify that some hash is the hash of your actual vote or something). This fails the obviousness property.

Blockchains don’t really bring much to the table here. They’re decent for byzantine fault tolerance in a space without a central authority, but elections do have some form of central authority and we’re not getting rid of that. The anonymity properties of blockchains can usually be achieved without blockchains for things like elections.

There are some kinds of cryptography that can be useful for auditability — zero knowledge proofs and homomorphic encryption come to mind — but you don’t need blockchains to use these, and using these still requires some form of technology as a key part of the voting system and this makes other properties of the system harder to achieve.

Become a poll worker!

It’s still a bit early for the next election, but I highly recommend you volunteer to be a poll worker for your county if you can!

It’s really fun, you get to learn about the inner workings of voting systems, and you get to meet a lot of people!

We had a cool kid come in and more or less do this at one point

Thanks to Nika Layzell, Sunjay Varma, Jane Lusby, and Arshia Mufti for providing feedback on drafts of this blog post.

-

Last year they required postage, but I they’ve changed that with a law this year. Yay! ↩

-

Ostensibly because of fears of voter fraud, but they’re largely unfounded — in practice this just reduces turnout ↩

-

I think for Alameda county the only such office is the Registrar of Voters in Oakland ↩

-

The crossing-off and signing lists are different, but this isn’t too important. ↩

-

I remember one particularly curmudgeonly voter loudly grumbling about all the propositions as they were voting. One doesn’t “vote” in California, one fills out social studies homework. ↩

-

I don’t quite recall how the verifiability works for people using the audio unit, they may be allowed to ask someone else to verify for them? ↩

-

If you vote in a different precinct, or worse, a different county, the ballot cards may not contain all the same races, so voting provisionally from the wrong district means that you only get to vote for the races common to both ballot cards. ↩

-

It’s imperative that these do not go into the scanner (since that operation cannot be undone), and to prevent this poll workers are instructed to not give provisional voters a secrecy sleeve as the envelope acts as a secrecy sleeve. Whoever is supervising the scanner will only allow people with secrecy sleeves to slip their ballots into the scanner. ↩

-

The exception is using the touchscreen machine, where you get to vote without using up a ballot card on voting day. However, tallies for the machine are kept separately, and I think these too are eventually turned into normal ballot cards. ↩