I’ve been thinking about this a lot these days. In part because of an idea I had but also due to this twitter discussion.

When teaching most things, there are two non-mutually-exclusive ways of approaching the problem. One is “proactive”1, which is where the teacher decides a learning path beforehand, and executes it. The other is “reactive”, where the teacher reacts to the student trying things out and dynamically tailors the teaching experience.

Most in-person teaching experiences are a mix of both. Planning beforehand is very important whilst teaching, but tailoring the experience to the student’s reception of the things being taught is important too.

In person, you can mix these two, and in doing so you get a “best of both worlds” situation. Yay!

But … we don’t really learn much programming in a classroom setup. Sure, some folks learn the basics in college for a few years, but everything they learn after that isn’t in a classroom situation where this can work2. I’m an autodidact, and while I have taken a few programming courses for random interesting things, I’ve taught myself most of what I know using various sources. I care a lot about improving the situation here.

With self-driven learning we have a similar divide. The “proactive” model corresponds to reading books and docs. Various people have proactively put forward a path for learning in the form of a book or tutorial. It’s up to you to pick one, and follow it.

The “reactive” model is not so well-developed. In the context of self-driven learning in programming, it’s basically “do things, make mistakes, hope that Google/Stackoverflow help”. It’s how a lot of people learn programming; and it’s how I prefer to learn programming.

It’s very nice to be able to “learn along the way”. While this is a long and arduous process, involving many false starts and a lack of a sense of progress, it can be worth it in terms of the kind of experience this gets you.

But as I mentioned, this isn’t as well-developed. With the proactive approach, there still is a teacher – the author of the book! That teacher may not be able to respond in real time, but they’re able to set forth a path for you to work through.

On the other hand, with the “reactive” approach, there is no teacher. Sure, there are Random Answers on the Internet, which are great, but they don’t form a coherent story. Neither can you really be your own teacher for a topic you do not understand.

Yet plenty of folks do this. Plenty of folks approach things like learning a new language by reading at most two pages of docs and then just diving straight in and trying stuff out. The only language I have not done this for is the first language I learned3 4.

I think it’s unfortunate that folks who prefer this approach don’t get the benefit of a teacher. In the reactive approach, teachers can still tell you what you’re doing wrong and steer you away from tarpits of misunderstanding. They can get you immediate answers and guidance. When we look for answers on stackoverflow, we get some of this, but it also involves a lot of pattern-matching on the part of the student, and we end up with a bad facsimile of what a teacher can do for you.

But it’s possible to construct a better teacher for this!

In fact, examples of this exist in the wild already!

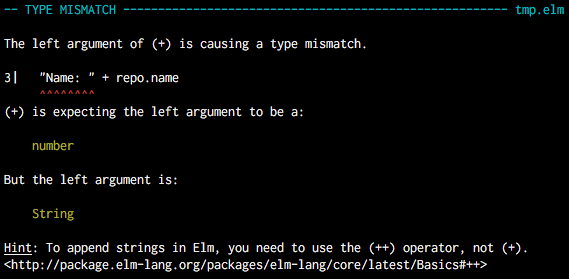

The Elm compiler is my favorite example of this. It has amazing error messages

The error messages tell you what you did wrong, sometimes suggest fixes, and help correct potential misunderstandings.

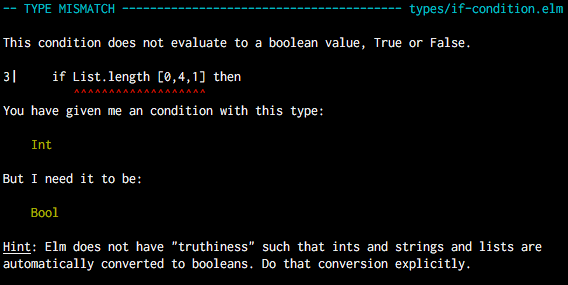

Rust does this too. Many compilers do. (Elm is exceptionally good at it)

One thing I particularly like about Rust is that from that error you can

try rustc --explain E0373 and get a terminal-friendly version

of this help text.

Anyway, diagnostics basically provide a reactive component to learning programming. I’ve cared about diagnostics in Rust for a long time, and I often remind folks that many things taught through the docs can/should be taught through diagnostics too. Especially because diagnostics are a kind of soapbox for compiler writers — you can’t guarantee that your docs will be read, but you can guarantee that your error messages will. These days, while I don’t have much time to work on stuff myself I’m very happy to mentor others working on improving diagnostics in Rust.

Only recently did I realize why I care about them so much – they cater exactly to my approach to learning programming languages! If I’m not going to read the docs when I get started and try the reactive approach, having help from the compiler is invaluable.

I think this space is relatively unexplored. Elm might have the best diagnostics out there, and as diagnostics (helping all users of a language – new and experienced), they’re great, but as a teaching tool for newcomers; they still have a long way to go. Of course, compilers like Rust are even further behind.

One thing I’d like to experiment with is a first-class tool for reactive teaching. In a sense, clippy is already something like this. Clippy looks out for antipatterns, and tries to help teach. But it also does many other things, and not all are teaching moments are antipatterns.

For example, in C, this isn’t necessarily an antipattern:

struct thingy *result;

if (result = do_the_thing()) {

frob(*result)

}

Many C codebases use if (foo = bar()). It is a potential footgun if you confuse it with ==,

but there’s no way to be sure. Many compilers now have a warning for this that you can silence by

doubling the parentheses, though.

In Rust, this isn’t an antipattern either:

fn add_one(mut x: u8) {

x += 1;

}

let num = 0;

add_one(num);

// num is still 0

For someone new to Rust, they may feel that the way to have a function mutate arguments (like num) passed to it

is to use something like mut x: u8. What this actually does is copies num (because u8 is a Copy type),

and allows you to mutate the copy within the scope of the function. The right way to make a function that

mutates arguments passed to it by-reference would be to do something like fn add_one(x: &mut u8).

If you try the mut x thing for non-Copy values, you’d get a “reading out of moved value” error

when you try to access num after calling add_one. This would help you figure out what you did wrong,

and potentially that error could detect this situation and provide more specific help.

But for Copy types, this will just compile. And it’s not an antipattern – the way this works

makes complete sense in the context of how Rust variables work, and is something that you do need

to use at times.

So we can’t even warn on this. Perhaps in “pedantic clippy” mode, but really, it’s not a pattern we want to discourage. (At least in the C example that pattern is one that many people prefer to forbid from their codebase)

But it would be nice if we could tell a learning programmer “hey, btw, this is what this syntax means, are you sure you want to do this?”. With explanations and the ability to dismiss the error.

In fact, you don’t even need to restrict this to potential footguns!

You can detect various things the learner is trying to do. Are they probably mixing up String

and &str? Help them! Are they writing a trait? Give a little tooltip explaining the feature.

This is beginning to remind me of the original “office assistant” Clippy, which was super annoying. But an opt-in tool or IDE feature which gives helpful suggestions could still be nice, especially if you can strike a balance between being so dense it is annoying and so sparse it is useless.

It also reminds me of well-designed tutorial modes in games. Some games have a tutorial mode that guides you through a set path of doing things. Other games, however, have a tutorial mode that will give you hints even if you stray off the beaten path. Michael tells me that Prey is a recent example of such a game.

This really feels like it fits the “reactive” model I prefer. The student gets to mold their own journey, but gets enough helpful hints and nudges from the “teacher” (the tool) so that they don’t end up wasting too much time and can make informed decisions on how to proceed learning.

Now, rust-clippy isn’t exactly the place for this kind of tool. This tool needs the ability to globally “silence” a hint once you’ve learned it. rust-clippy is a linter, and while you can silence lints in your code, you can’t silence them globally for the current user. Nor does that really make sense.

But rust-clippy does have the infrastructure for writing stuff like this, so it’s an ideal prototyping point. I’ve filed this issue to discuss this topic.

Ultimately, I’d love to see this as an IDE feature.

I’d also like to see more experimentation in the department of “reactive” teaching — not just tools like this.

Thoughts? Ideas? Let me know!

thanks to Andre (llogiq) and Michael Gattozzi for reviewing this

-

This is how I’m using these terms. There seems to be precedent in pedagogy for the proactive/reactive classification, but it might not be exactly the same as the way I’m using it. ↩

-

This is true for everything, but I’m focusing on programming (in particular programming languages) here. ↩

-

And when I learned Rust, it only had two pages of docs, aka “The Tutorial”. Good times. ↩

-

I do eventually get around to doing a full read of the docs or a book but this is after I’m already able to write nontrivial things in the language, and it takes a lot of time to get there. ↩